ATHABASCA — In December 2020, one of last remnants of physical evidence of the settlers who made their homes in Amber Valley, east of Athabasca, burned to its foundation, leaving nothing but memories and ash.

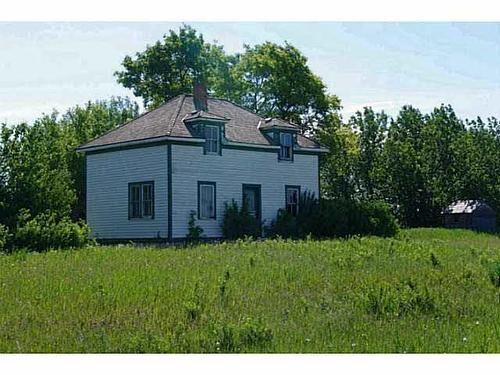

The house, christened Obadiah Place, was on the same land owned by Willis Bowen, and replaced the log cabin he had built in 1913 with an updated wood-siding, one-and-a-half-story home in 1938 by its namesake, Willis’ son Obadiah Bowen, and was designated as a historical site by the province in 1999.

The elder Bowen arrived from Oklahoma during the second wave of Black immigrants from the United States, who were attempting to escape the rampant, systemic racism of the American South, and recently enacted Jim Crow laws.

“He stopped in Vancouver for three years, I believe it was,” said Willis' granddaughter Myrna Bowen-Wisdom in a recent interview. “And I was just going over some of the information and I note that he filed for his homestead in 1913, which would have been about three years after the first (group of) people came.”

After the American Civil War, the southern states enacted what became known as Jim Crow laws in 1877. The name is reportedly based on a black-face character created by actor Thomas Dartmouth Rice that used exaggerated language and tended to perpetuate negative stereotypes.

The laws imposed segregated Black communities, and dictated not only where they could live, but where they could use a bathroom, drink from a fountain, go to school, bury their dead and more, and were not officially overturned until the mid-1960s.

Many headed north to Canada, hoping for a better life, free of being judged by the colour of their skin. Some headed east to the Maritimes, while others made their way west to the prairies — and that is how Amber Valley, initially called Pine Creek, was formed.

Between 1909 and 1911 an estimated 1,000 to 1,500 Black men, women and children settled across Canada, mainly in Alberta and Saskatchewan establishing roots in Amber Valley; Junkins, now Wildwood; Breton, formerly Keystone; and Campsie, west of Barrhead, where a segregated cemetery east of Thunder Lake still remains.

By 1910, approximately 300 settlers were in the Amber Valley area and Willis Bowen, his wife Jeanne, who passed away in 1932, and his 12 surviving children expanded that number even further. The Bowens lost two daughters as infants, but the family consisted of Mary, Willa, Ivy, Reese, Boadie, Geoffrey, John, Obadiah, Elrene, Edward (Eddie), Purvis (P. K.) and Jean.

Bowen-Wisdom said her father, Reese, was about 12 years old when the family arrived on the homestead, and his older siblings, Mary and Willa worked away from home to provide income.

“Aunt Mary and Aunt Willa, they were the two oldest girls and the schooling that they obtained would have been from Oklahoma,” Bowen-Wisdom said. “After they came here, they had to work and help support the family.”

The Bowen family quickly established themselves in the community, even as many Canadian politicians aimed to start limiting immigration of Black settlers by imposing strict requirements not applied to other immigrants — a minimum of $200 cash-on-hand, per person; excellent health; literate; and documented proof of good moral standing were just a few of the hoops they had to jump through.

Willis’ original log house went on to become a gathering place for the community, and his grandson, Dennis Bowen, son of Obadiah, recalls his grandfather often having visitors.

"Neighbours would visit him and they would sit in the living room with, you know, old pioneers that came up. It was a good time,” Dennis said.

Dennis grew up 100 yards away from his grandfather's home, and recalled the telephone booth that sat on the corner of the two properties with a line running to the house.

“For long distance calls and to handle incoming calls or messages, we had a phone in our house that was connected with the phone line,” he said. “The only way a person in Amber Valley could get a message over the phone was to come to our home or it had to be delivered.”

The Bowen patriarch, who was almost 101 when he passed away in 1975, went on to become the first Black postmaster in Alberta when he took over the post office in Amber Valley. He was also a deeply religious Christian who walked everywhere, recalled his grandchildren.

“He used to walk up to our house and have breakfast and mom used to drive him to and from Athabasca. I don't think he ever owned a car, because somebody always drove him around,” said Bowen-Wisdom. “But he was very active in the church and he was active in getting the school board going and in later life, he turned these things over to the younger people. His involvement was mainly in the church.”

Obadiah was also well-known and very active in the community, and was pastor of an interdenominational church that was built on land he donated about a half-mile from the original homestead in 1953.

Slowly the community scattered to the wind as the children grew up and moved away from the prairie life of farming, but the accomplishments of the children and grandchildren of those Amber Valley settlers have hardly faded from history. Willis’ grandson Oliver managed the design and construction of Calgary’s first light, rapid transit (LRT) line. Award-winning author, playwright, screenwriter and documentary film maker Cheryl Foggo has ties to Amber Valley, as did Violet King Henry, the first black woman lawyer in Canada, and Floyd Sneed, the drummer for Three Dog Night.

In 2017, Obadiah Place and the 3.6 acres it sat on, was listed for $39,900 and sold for an undisclosed sum to buyers from Fort McMurray who were working with the Heritage Division of Culture and Tourism to restore and upgrade the 85-year-old house.

And now that home is lost forever, something the president of the Amber Valley Historical Society (AVHS), Gil Williams, feels deeply as there had been some discussion of the historical society purchasing the house, to be a museum or other point of interest.

“It’s just too bad," Williams said. “It’s too bad we never got it into our hands and that we didn’t work on it.”

Gary Chen with the Heritage Division of Culture and Tourism, the part of the Alberta government that designates historic sites called the loss “a tragedy.”

An investigation into the cause of the fire is still ongoing, but nothing will bring back that piece of Canadian history.