ATHABASCA – Even without getting into how hydrogen and oxygen atoms come together to create the water molecules that nourish every living creature on Earth, or how those molecules change their physical state from solid, to liquid, to gas as part of the planet’s water cycle, the story of how the clean, cool, crisp water you drink appears before you with the mere turn of a tap is one that still spans millions of years.

The process is similar in any town or region where you may reside - intake, treatment and distribution - but the details rely mainly on where the water comes from before it starts its journey through the pipes. For customers of Aspen Regional Water Services, that source is the Athabasca River, or more precisely, the Columbia Icefields in the Rocky Mountains that straddle the border between Alberta and British Columbia.

Over the last two million years, there have been 80 glaciation cycles that have seen ice sheets expand and contract and merge with each other. The meltwater from those ice sheets is responsible for many of the lakes and rivers that exist in the Athabasca River basin today as the overflow that trickled down the mountain crevices to the north then the eastern slopes soon became a stream, and then the mighty Athabasca River that now makes its way 1,231 km across Alberta, all the way to Lake Athabasca before its waters set a course north down the McKenzie River, all the way to the Arctic Ocean.

By the time it reaches the Town of Athabasca and enters the regional water system, that water has already flowed through Jasper, Hinton, Whitecourt, along with any number of villages, hamlets, farmsteads, and other communities along the way before it heads north to Fort McMurray and beyond.

Depending on the time of year and a host of other variables, the soon-to-be-replaced raw water intake at what was once the town’s water treatment plant, on the edge of the river near the Tipton’s Your Independent Grocer store, has been living up to its name with varying degrees of reliability for decades. In its last functional year, the current system is getting a relatively easy ride into retirement, with river water that is already very clear, with very little debris.

“The colour is radically different than last year. This year, the creeks and the tributaries are contributing very little, so you can actually see a change in colour in the river; there's more of what I call the mountain influence. And after Athabasca, it starts to drop to lower land and you get more of a muskeg influence, so we're right on the edge of things, sometimes we get raw water that is harder to treat and right now, with the more mountain/foothill influence we get clearer water,” said Aspen Regional Water Services Commission manager Jamie Giberson July 15, as he and commission chair Kevin Haines provided an exclusive tour of the 60-plus-year-old building as it is completely renovated and modified inside to accommodate a new raw water intake system.

“Everything upstream of here influences the quality of the raw water, and we notice it significantly, our operators really pay attention to that,” he added, noting also that while the river was exceptionally high at this point in 2020, this year with little precipitation and an early melt, it is at one of the lowest lows he has seen, which bodes well for the project.

From outside, it just looks like any other renovation project – it’s fenced off; there's a large industrial garbage bin outside; a skid steer; and a port-a-potty for the hard-hat wearing construction workers who go about their work inside and outside of the building all day. Soon though, the work on the actual mechanism that draws the water into the building will begin with barges on the river and specialized divers beneath.

The raw water intake upgrade is something that has been on the commission’s wish list since the new plant was built in 2010, said Haines.

“This has really been kind of a bottleneck for us for quite a while; the issues of getting the water into the plant and the issues with the sand and everything else, but also not being able to pull the water properly,” he said, noting the intake has never been able to provide as much water as the new plant is capable of handling.

However, grant funding - an Alberta Community Resilience Program (ACRP) grant for $1,518,000 from the province, and an Investing in Canada Infrastructure Program (ICIP) grant for $1,043,000 from the federal government that were expected to cover the total $2.7 million cost along with a $608,720 contribution from the commission’s capital reserves - weren’t in place until late September 2020.

Six months later, the project had been tendered, with a low bid coming in at $4,742,287, and with engineering costs included, the cost was now $5.17 million.

At the water commission’s April 6 meeting, representatives from the partner municipalities of the Town of Athabasca, Athabasca County and Village of Boyle got the news and were tasked with going back to their respective councils to try to figure out a way to come up with the additional funds before the grant money expired.

Based on each municipalities’ historical usage, the town was now on the hook for an additional $1.26 million (63 per cent), which it borrowed with a 30-year debenture; the county used $340,000 (17 per cent) from its water equipment and upgrade reserve; while the village also took out a debenture, this one for $400,000 (20 per cent) over five years.

The current system sees a 400-foot pipe extend from the building into the river. Gravity forces the water through the pipe and into a 35-foot deep wet well on the north side of the building. The upgrade will essentially increase the size of everything – the pipe will extend further into the river and filter out more debris, preventing blockage and unnecessary wear-and-tear on the pumps inside the building. The size of the wet well will be up-sized considerably too.

“We've had lots of issues where we don't get enough flow in, to the point where last spring the intake line was completely plugged off, so we had no water coming in, so the town helped us out with their hydrovac and on a wing and a prayer, it let go, and we were good again,” said Giberson.

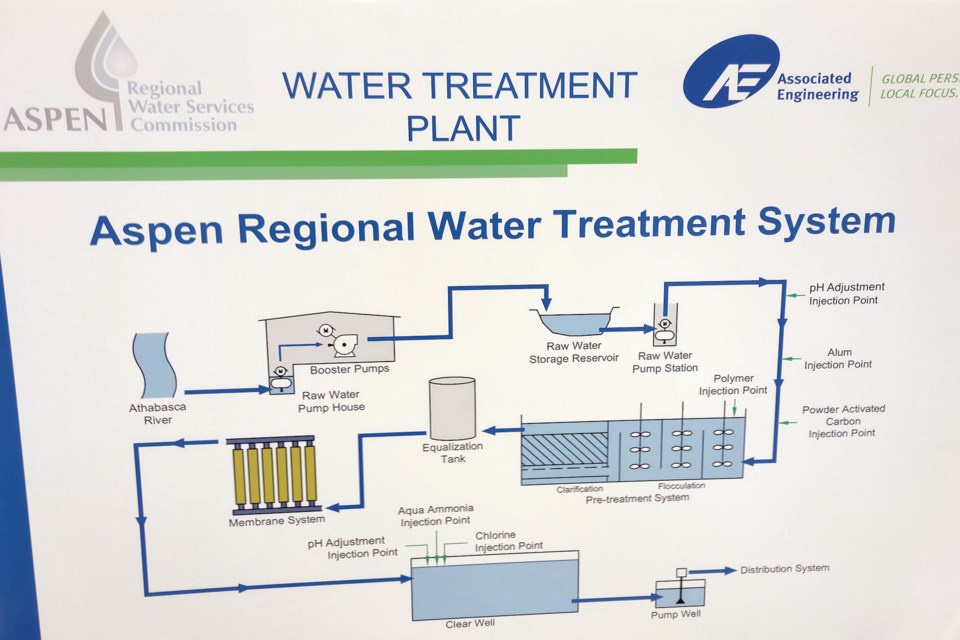

Once inside the building, a grinder takes care of any larger pieces of debris, then a sand separator does its job, and the water is sent to the upper level of the building to the booster pump, which sends the water through the pipe up to the new water treatment plant at 5306 Woodheights Road.

The new intake pipe will screen out much more debris and new sand separators promise to be much more efficient, which will help prevent many of the issues the current system has faced recently as it approached the end of its service life. During the flooding that occurred in the summer of 2020, for instance, the basement of the facility was itself submerged in a couple feet of water.

The current system sees a submersible pump feed pressure to the booster pump, but the new system will see the submersible pump dump into tanks and vertical turbine pumps will then provide enough pressure of their own to send the water up the hill to the treatment plant - with even more sand and solids removed from the raw water, the vertical turbines will also have a much longer lifespan than the boosters currently in use.

Added Giberson: “I'll tell you what - as the person who's responsible for it, when that intake plugs off, the stress goes really high, real fast because you're dealing with the town, the county, the village, everyone relies on whatever comes through and when nothing comes through that pipe, that gets exciting.”

Over the rest of the summer, as the new intake system is installed, the Advocate will continue to follow the water for its entire journey, as it is pumped up the east hill to the Aspen Regional Water Treatment Plant to be stored and treated before it is distributed to residents of Athabasca, Colinton, Boyle, Grassland, Wandering River and many points in between.