WESTLOCK - Westlock County is looking for options to create a more reliable flood hazard map for the Pembina River, but options are costly and provincial support is lacking.

After residents complained last summer about a restrictive flood plain overlay in the municipal development plan (MDP), council modified the document, moving the overlay to the land-use bylaws and accommodating for buildings of agricultural use.

However, the issue of the map, which details the extent of a possible flooding during a one-in-100-year event around the river, thus delineating the areas included in the overlay, has yet to be solved. At the same time as modifying bylaws, council also struck up a six-person Flood Hazard Area Development Advisory Committee (two residents within the flood plain, two outside of it, and two councillors). Their task is to find options for the county moving forward.

“The existing flood map is too inaccurate,” said deputy reeve Brian Coleman at the committee’s Jan. 17 meeting.

There is some confusion about how the county incorporated that flood plain map into its documents in the first place.

The 1998 land use bylaw states, “Alberta Municipal Affairs identified a 1:100-year flood plain. That area is shown in the municipal development plan.”

This is repeated in the 2003 version.

“It shall be the responsibility of any developer who develops in the proximity of the Pembina River to ensure that the development occurs in such a manner as to be satisfactorily flood-proofed and flood-protected. The municipality and the development authority shall take no responsibility in this regard.”

The above is the extent of county regulations regarding building near the Pembina River, in effect until the passing of the 2016 MDP, which included the much maligned and recently modified overlay.

In response to an inquiry from the Westlock News, both Environment and Parks (on Jan. 17) and Municipal Affairs (Feb. 13) confirmed that the province did not provide a map to the county.

“Our understanding is that the flood overlay used by Westlock County … was created by the county based on aerial photography of the 1986 flood, which was supplied by the province,” said Environment and Parks press secretary Jess Sinclair via e-mail.

Timothy Gerwing, Municipal Affairs press secretary, repeated the above statement in an e-mail last week.

The core of the problem is precisely this map. Regardless of who created it, the data behind it is insufficient.

This is what the committee is attempting to correct, but getting to the stage of a clear and scientifically foolproof (or at least complete) map is costly.

As it came out during the committee’s meetings, a possible GIS study of the river could reach $500,000.

Alberta Environment and Parks runs a flood hazard identification program. Some form of flood hazard mapping has existed at the provincial level since the 1970s, according to the ministry’s website. Part of this program is the mapping of flood hazard areas using GIS technology.

Across the province, 21 new projects have been commissioned since 2015, among them areas of the counties of Athabasca and Slave Lake. A portion of the Paddle River that runs through Barrhead (both town and county) is already provincially mapped, so is Athabasca River through Athabasca.

“Currently, there are no plans for any new provincial flood hazard mapping studies in Westlock County,” added Sinclair in response to a question about whether or not Pembina River is a candidate.

He added that “we have shared this position with the county” as recently as early 2019 – it’s unclear if this was at the county’s inquiry or of their own volition.

As it stands, there seems to be no recourse for Westlock County to access some level of support from the province through the direct and obvious avenues: flood programs.

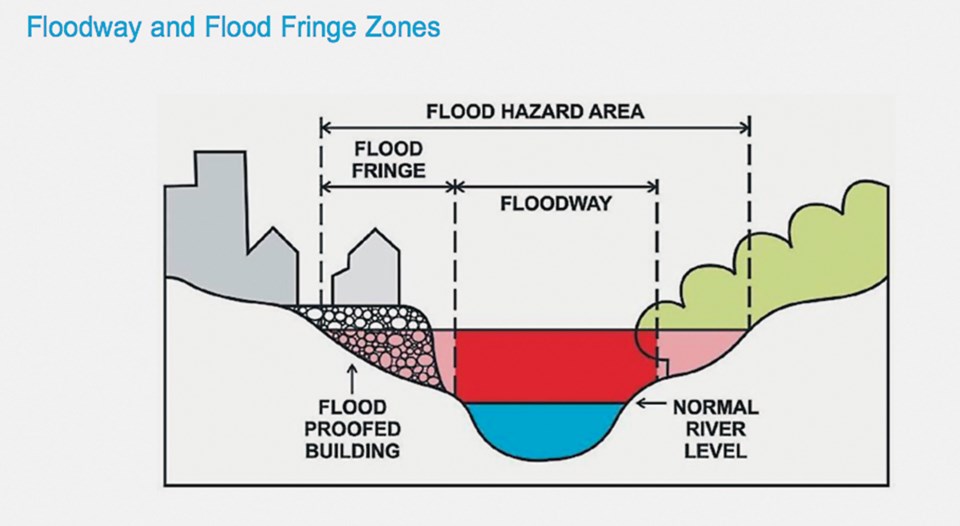

There is one corollary to the lack of provincial mapping on a river: “municipal governments currently make decisions about developing land under their jurisdiction, including floodways. Development decisions are governed by each municipality’s land use bylaw,” said Gerwing.

In essence, as Municipal Affairs and Environment and Parks both say (again, ad literam) it’s within a provincially mapped floodway that the Municipal Government Act gives the provincial government the authority to create development regulations.

In this case, the province cannot dictate how the municipality deals with development in floodways because it hasn’t determined the area to be a floodway in the first place, contrary to CAO Leo Ludwig’s insistence last year while the issue was in full swing.

During a public hearing Sept. 10, 2019 for the new overlay and exemptions to it, Ludwig said the province wanted “full-on prohibition” on building in floodways. Currently there is no recourse for the government to impose development regulation since it hasn’t committed to mapping the river, at least according to the two ministries.

As for floodway development regulations, those are still “being considered,” also confirmed by both press secretaries.

What about now?

In the meantime, the six people on the flood advisory committee are looking for a number of options to supplement what seems to be provincial inaction, delay, or simply cost constraint.

One of them is a comprehensive GIS study of the river that would result in a definitive flood plain map.

Data collection (river specificity, hydrological assessments, culvert analysis, etc.) is the most expensive part of accurately flood mapping an area, which is what Michael Florendo, engineer with McElhanney, told the committee via conference call at their Jan. 17 meeting.

The field component of the $500,000 GIS project would cost between $300,000 and $400,000 — that would include things like LiDAR to determine topography, and sonar for the bottom of the river.

There is a more economical option, Florendo said, that would take into account topographical data that’s already available, run through updated climate, watershed and hydrological data points.

“That’s kind of a middle step because we are using historical data as opposed to getting updated data” for topography and it would cost the county $55,000.

This second option is likely to produce a more conservative flood plain than a comprehensive GIS study would, since 100-year flows, said Florendo, are smaller now than they used to be. Given that the cheaper option uses historical data, the flood plain would be wider than the one obtained via GIS.

Provincial grants are available, and McElhanney has applied for them for other municipalities, but it’s based on the value of the projects that are applied for. The fact that Pembina is not currently a candidate for flood mapping says something about the value it has provincially.

For now, the flood advisory committee decided to test LiDAR mapping (Light Detection and Ranging) on two properties on the river at a cost of $440 per square kilometre.

According to Altalis, the Calgary-based company that will be providing the service for the two properties, LiDAR uses laser, GPS and inertial technology to create, in this case, a digital elevation model.

As Florendo suggested then, any LiDAR mapping can be integrated into an updated flood model.

“We use industry-standard software. For the most part, it’s free … it’s accurate, pretty easy to use. It’s been around for at least 20 years. Any time there’s updated topography or updated river imagery, it can be added into the model, then quickly spit out an updated flood plain level.”

In essence, if the county decides to get a flood model made for $55,000, it can be updated every time a property owner who wants to develop gets LiDAR mapping on the property.

At the last county meeting Feb. 11, Janet Pomeroy, executive director of the Athabasca Watershed Committee, presented to council the newest plans that organization has for the Pembina River.

As a tributary of the Athabasca River, Pembina is one of its sub-watersheds. The committee received a $250,000 grant (spread over three years) to conduct studies of riparian health — riparian areas exist between streams and land.

The objective is to mitigate flooding (among other things) through vegetative health in those riparian areas, but part and parcel is a GIS study of the watershed.

The North Saskatchewan Watershed Committee has already conducted some studies in this area, “a detailed land covered dataset,” the first stage to a complete GIS study, said Pomeroy. Next comes an assessment of riparian health 50 metres from the river’s edge, but she suspects they’ll concentrate on their own watersheds.

As Florendo told the flood committee, any studies in the area can be used for a flood model, but Pomeroy did advise that their own data collection is specifically focused on riparian health and might not provide the same data sets needed for flood mapping.

Andreea Resmerita, TownandCountryToday.com

Follow me on Twitter @andreea_res