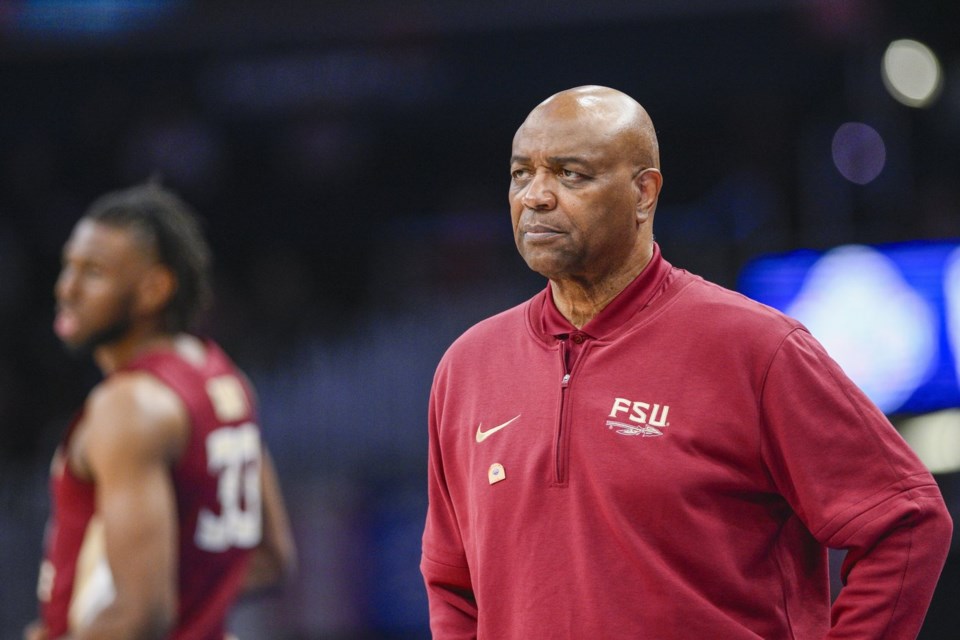

More than the deep runs in March Madness, the 660 victories over 37 years or even the 20 or so players he coached who ended up making millions in the NBA, Leonard Hamilton is proud of a number he can count on one hand.

It is, he says, the number of players he coached at Miami, and then for the past 23 seasons at Florida State, who failed to graduate.

Hamilton, now 76 and stepping away from a business he barely recognizes anymore, says he is at peace with leaving coaching behind. More than a dozen other coaches interviewed by The Associated Press leading up to this year's NCAA tournaments expressed concern about the future of their industry. Most said they still liked their jobs, but it has taken some adjustments.

“What I have learned is, the skill set that was required to be a good coach 10 years ago, very little of that applies anymore,” said Buzz Williams, who spent six years at Texas A&M and on Tuesday was named the new coach at Maryland.

Coach after coach, from Miami's Jim Larrañaga to Virginia's Tony Bennett to Villanova's Jay Wright and others have all walked away from the game, saying it no longer holds the appeal it once did. Some specifically blamed the transfer portal for the added stress — Michigan State coach Tom Izzo last week called the portal a “urinal” — and of course the pressure to compete for players with endorsement money, a topic that stretches beyond basketball.

Most of those coaches made comfortable careers in college, some of them earning big paychecks, and some of their replacements are doing just fine. But there is no way around the fact that many feel their profession is becoming difficult to manage in its current state and certainly doesn't have the same feel-good goals it once did.

Answers? Williams doesn’t have them, other than “this upcoming season is going to be different from the last season.” Hamilton insists he doesn’t have answers either for a college sports landscape that feels more like a talent auction every day. Only questions.

One of them: “Is this what we want in college sports, people going to the highest bidder?” he asks. Hamilton said he will not answer that question, lest he be painted as a coach who left because he is against paying players.

Untethered from the prospect of having to lure those players to a program anymore, though, he can ask the questions in ways many other coaches can’t -- or won’t: “Have you heard anybody talk about academics lately?” he said.

From APR to NIL

Final Four week used to be a week that induced handwringing over one of college basketball’s most defining metrics: The Academic Progress Rate (APR) scores would be held up as a North Star for programs that did things the “right way” or as a cudgel for those that didn’t, with the NCAA able to slap sanctions.

Debates on the road to the title would revolve around whether those still playing were the best examples of schools that produced “student-athletes,” to use the NCAA's increasingly anachronistic term, or simply churned out one-and-dones who could come, contribute to a title run, then head for big bucks in the pros.

These days, big bucks are available in college. The APR still comes out each June, but its relevance has been replaced by a new entry in the NCAA’s cauldron of alphabet soup: NIL.

The numbers attached to the name, image and likeness deals are now what get the most attention. They are the most telling indicator of a program’s health and the main consideration – maybe the only consideration – when it comes to adding players from an increasingly packed transfer portal or simply keeping them on your own roster.

UCLA coach Cori Close, who is taking the program to its first women's Final Four, says the Bruins have all the advantages they need to stay competitive.

“That being said, globally, I do wonder if we are eroding the true lessons that stay with young people for the rest of their lives," Close said. "My biggest commitment in being a coach is preparing young people for life after basketball and I sometimes worry ... we’re eroding some of the character building that I think is really what’s most special about college athletics.”

Judge's ruling to set table for new era

Next Monday, a federal judge will hear final arguments before deciding whether to approve the House settlement, a $2.8 billion plan that will add a new layer of change to an already unstable landscape.

If Judge Claudia Wilken approves the settlement as expected, then for the first time, schools will be allowed to share TV, ticket and other revenue to the tune of around $20.5 million per year per institution with their athletes. That will be in addition to the payments already allowed from third parties that are turning college players into millionaires.

Duke’s Cooper Flagg, the biggest star in the men’s college game and the favorite to cut down the nets in San Antonio a few hours after that hearing, is making an estimated $4.8 million via NIL deals. Next year, five-star recruit AJ Dybantsa is expected to play at BYU on a deal reportedly worth $7 million.

If the settlement is approved, the new rules will go into play on July 1. The schools – even the biggest and best organized – are scrambling to put the pieces in place.

“We’re not ready to go, and I think if anybody says that they are, they’re not telling the truth,” Michigan athletic director Warde Manuel said. “We’re getting nearer to being ready to go.”

Life as a coach means change

As leader of one of the wealthiest athletic departments in the country, with a donor base that matches its storied tradition, Manuel has things relatively good.

Last year, when the Wolverines were coach shopping, they made a run at Florida Atlantic coach Dusty May — he was fresh off his team's magical run to the Final Four — and had the resources to land him. One of May’s top players at FAU, Vlad Goldin, and one of his top recruits, LJ Cason, came with him.

That sort of churn, from the smaller school to the bigger one, is now a daily occurrence in college basketball.

At Northern Colorado, Steve Smiley came oh-so-close to the program's second March Madness appearance last month. The Bears, playing in the Big Sky Conference, are a solid program that occasionally nabs a great player.

Two seasons ago, that player was Dalton Knecht, who blossomed and averaged 20 points and seven rebounds. A year later, he was making bigger money at Tennessee on his way to the NBA. Last year, the diamond in the rough was Saint Thomas, who came to Northern Colorado from Loyola-Chicago. This season, he played for Southern California.

“I still enjoy coaching every bit as much as I ever have,” Smiley said. “But I’m from the small colleges, I played Division II basketball, I coached at junior college and a lot of different levels before getting to this one. You wear a million different hats, and you grow with that idea, and it’s helped us be able to adjust to all the movement and change.”

Show me the money

Back in 2010, Tad Boyle left Northern Colorado to move down the road to University of Colorado. He has spent those years turning the Buffaloes into a semi-regular contender. But not this year.

In a season that flew far under the radar at a school where Deion Sanders’ reinvigoration of the football program is hogging the attention, Boyle went 14-20 after losing six players to the NBA and the transfer portal.

Boyle, as always, was handed a ballot to vote for his conference’s coach of the year at the end of the season. This year, he refused to fill it out. He said there was no way to assess who did a good job unless you knew how much money their programs had to pay players.

“We know what the Kansas City Royals payroll is. We know what the New York Yankees payroll is, and then we can judge whether the Royals have a better year than the Yankees based upon that," Boyle said in drawing an analogy to a relatively transparent system that does not exist in college sports.

What are the rules and who enforces them?

Even if schools are freed up to spend $20.5 million on players under terms of the settlement, that money will be distributed in different ways to players in different sports – mostly football and men’s and women’s basketball.

While there are plans for an enforcement body to make sure everyone follows the same rules, even its role is murky with the launch only three months away.

The payments will come from the schools -- above the table -- but the general lack of transparency in college sports put a disconcerting spin on Hamilton’s departure from Florida State. Late last year, six players sued the coach, claiming he did not make good on promises to pay them NIL money in a dispute seen elsewhere this past season.

The school has denied wrongdoing. Hamilton doesn’t talk about the lawsuit. He is more comfortable asking questions about the world that created it.

“You can’t be the president of Chrysler today and the president of Ford tomorrow. You can’t play for the Lakers on Monday, then go play for the Clippers on Friday,” Hamilton said. “And somebody needs to be accountable for the chaos and explain what the thought process is of how we’re supposed to deal with all this. There has to be a structure. That’s how you keep order in society.”

___

AP Sports Writers Pat Graham, Michael Marot, Teresa Walker, Eric Olson, Larry Lage and Steve Megargee contributed to this report.

___

AP March Madness bracket: https://apnews.com/hub/ncaa-mens-bracket and coverage: https://apnews.com/hub/march-madness. Get poll alerts and updates on the AP Top 25 throughout the season. Sign up here.

Eddie Pells, The Associated Press