When Jack Preece wrote a letter to his sister Lillie on Dec. 14, 1917, he opened with what a brother might always remark upon: how she was settling into married life, how her family was coming along.

But the bulk of the letter — written in a fine, slanting hand on Canadian YMCA stationery — was devoted to the Battle of Vimy Ridge in which he had fought that spring.

“The whole of the Ridge was illuminated by thousands of … lights and star shells & innumerable lightning-like flashes from the guns with the incessant roar of intensified thunder — surely an appalling and awe-inspiring sight,” Preece wrote.

Preece’s granddaughter, a 65-year-old Athabasca resident, recently rediscovered the letter.

“I put it away about 10 years ago … and I came across it the other day,” she said.

“They ended up after the (First World) War in Athabasca,” she said of her grandparents. “Because they were both in the war, they gave them … an option to homestead land or something. They came up here and found this piece up here.”

Preece praises his beloved — the Athabasca woman’s grandmother — in the letter, saying he urged her to leave London as the air raids become more frequent but missed her terribly once she left for Canada.

“She is the best little woman in the world, big-hearted and affectionate & an admirable house manager; I am looking forward to the day when we shall be together again in beautiful old Vancouver,” he wrote.

Preece had plenty of time to reflect on forthcoming domestic bliss; he spent six-and-a-half months convalescing in an Epsom hospital when his arm was wounded just three weeks after he fought at Vimy Ridge.

“He never got shot,” his granddaughter pointed out. “His horse got shot out from under him, and he fell to the ground, and there was barbed wire there that wrapped around his arm and tore his arm.

“I guess they were firing cannons … and they were taking turns with the horses taking the ammo across, and they would wait ‘til the enemy shot, and then they’d send somebody across, and then they’d wait for another shot, and they would send someone across. And I guess the Germans were catching on to this, and then when he went across, they shot again right away, and they shot his horse out from under him.”

In his letter, Preece devotes little space to his injury. His focus is firmly on Vimy Ridge.

“I was lead driver in our team & it was up to me to pick the way — a hopeless task — suddenly you feel your horse sink in under you as you plunge into a huge crater & feel the water rise to your knees & all the while those infernal shells turned the whole countryside into a hell.”

His granddaughter said Preece lived until his late 60s. She was five or six when he died, and the letter afforded her a glimpse into his life she would not have otherwise had. She was especially struck by his fine handwriting and articulate mode of expression, considering he had never gone to school.

“Now that they’re talking about post-traumatic stress disorder … I would think if anyone would have had it, somebody like that would have probably had it, but I don’t remember him ever being angry with us or being mean or anything,” she said.

Preece’s letter is just one part of her family’s history with war.

“My husband’s grandfather was … a prisoner of war. And then my other grandfather was a pacifist. So we come from the whole conglomerate, I guess,” she said.

For Preece, an equally varied composite image of Canada helped him make it through Vimy Ridge.

“We thought of the wild prairies … canoes or the huskies mushing along the snow trail, the sunset in the Pacific, Saturday afternoon at English Bay or the theatre — all these thoughts would conjure up pleasant visions of congenial surroundings while ahead of us in the full glare of the star shells was no man’s land pitted every inch with shell holes full of stagnant water with many a body rotting in it,” he wrote.

The full letter is below. To view photos of Jack and Bell Preece, click on the photo above, then click through the slide show.

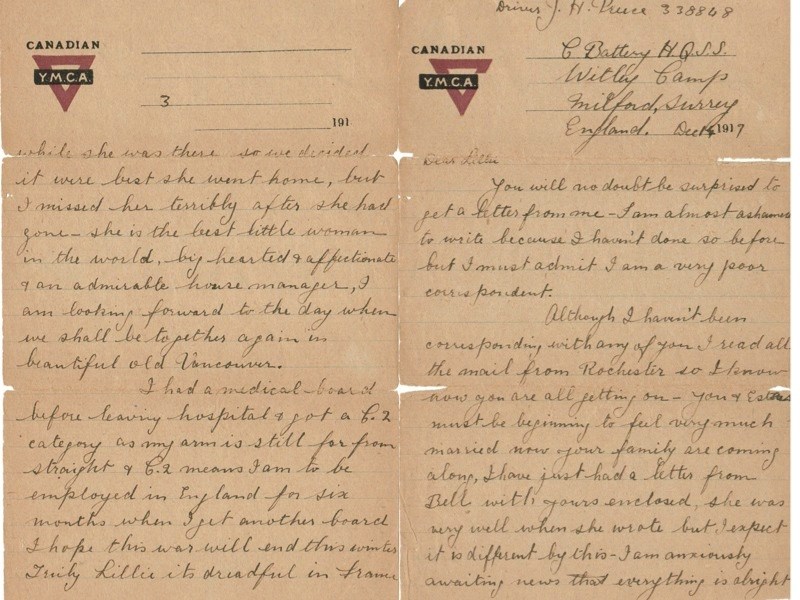

Driver J H Preece 338848

C Battery HQSS

Witley Camp

Milford, Surrey

England December 14, 1917

Dear Lillie

You will no doubt be surprised to get a letter from me - I am almost ashamed to write because I haven't done so before but I must admit I am a very poor correspondent.

Although I haven't been corresponding with any of you I read all the mail from Rochester so I know how you are all getting on - you and Ester must be beginning to feel very much married now your family are coming along, I have just had a letter from Bell with your enclosed, she was very well when she wrote but I expect it is different by this - I am anxiously awaiting news that everything is alright.

Of course you know I have been to France and got wounded on the first of last May I was in hospital six and a half months then I had twelve great grand and glorious days leave were twelve long days of bliss.

Latterly I was in an hospital in Epsom just a bus ride out of London & Bell was staying in London, I used to spend every weekend with her in our London home & she generally got out to see me during the week, but the air raids became so frequent & dangerous that I advised her to go back to Vancouver, every raid was a source of worry to me while she was there so we decided it were best she went home, but I missed her terribly after she had gone - she is the best little woman in the world, big hearted and affectionate & an admirable house manager, I am looking forward to the day when we shall be together again in beautiful old Vancouver.

I had a medical board before leaving hospital & got a C2 category as my arm is still far from straight & C2 means I am to be employed in England for six months when I get another board. I hope this war will end this winter. Truly Lillie it's dreadful in France. I consider I was extremely fortunate to get away alive my horse was killed under me & the same shell crippled my arm, we had taken the Vimy Ridge three weeks previously. I got my Blighty in the ruins of Theilus village on the Ridge.

I shall never forget the 9th of April at 5-30 am when the big drive started in the evening of the 8th I was detailed tot take ammunition to the guns we started at 7 pm it was bitterly cold with a dirty wet sleet driving before a half hurricane, we started from Mount St. Eloy taking the LaFaggete road running parallel with our line. The whole of the Ridge was illuminated by thousands of very lights and star shells & innumerable lightening like flashes from the guns with the incessant roar of intensified thunder - surely an appalling and awe inspiring sight.

We all knew that at 5-30 in the morning the big attack was to start - the support trenches was packed with troops & dense masses moved along the roads going up ready for the great push in the morning - one steady stream of dark forms moving along the side of the roads to disappear further on into dungeon like holes on the side of the road through subterranean trenches to the front line.

Sometimes our column of ammunition wagons would be at a standstill for hours owing to a jam in the traffic ahead - all the while Fritz was groping with big shells along the road the third team ahead of me got wiped out & where but a moment before were 6 horses three drivers & two gunners nothing remained but mangled horse & human flesh & the wreakage of limber. We dare not dismount or we would get shot we must sit our terrified horses & hope that the next would miss us which it did or I wouldn't be writing this today.

After nearly 4 hours of this nerve trying ordeal we started moving again, it was a relief to be doing something although the crump and coal boxes were wining overhead - we eventually reached our battery - we dare not show a light or even smoke & the darkness was intense, we had to cross a ditch with the mud up to the horses bellies here we had to use whip & spur to incite the poor brutes to clear it - the ground here about was pitted with shell holes, I was lead driver on our team & it was up to me to pick the way - a hopeless task - suddenly you feel your horse sink in under you as you plunge into a huge crater & feel the water rise to your knees & all the while those infernal shells turned the whole country side in to a hell.

We had orders to get our loads off as soon as possible & beat it as quick as we knew how - & we did. We had our horses at a dead gallop when down plunged my team into another hole & the other teams on top it’s a marvel we didn't get our necks broken, after a while we got the poor devils out when plunk came another trouble in the shape of a Jack Johnson Shell, instinctively your tendons & muscles become terse & set with the expectations of a rise in the world it buried itself about twenty yards from us in the soft earth - then of a sudden the end of the world seemed to have come, but we didn't get hurt the whole bunch of us was nearly buried in mud & earth after some delay we got started again & struck the road - say now - you should see us guys going some - with all my wet condition believe me I was sweating it oozed out of me like fat from a suckling pig.

We got back to our lines at 4 am had a shot of rum handed out to us - but instead of going to lie down we got to the edge of the wood to watch the opening of the big attack.

All along the Ridge one could trace the enemies lines by the burst of thousands of shells - but that was nothing only the ordinary desultory firmy - the Huns were only sending over occasional shells little dreaming of the immense powers concentrating behind our lines to drive him from that sepulcher of thousands of our bravest boys - that dark forbidding Mass - today the sentinel of the powers of darkness tomorrow the bulwark of civilization for this was the morning that our boys were to take it & we never doubted that we could.

These were intense moments the few minutes before the attack & it were no sign of weakness that our thoughts should turn to home & of our loved ones there - for we well knew that thousands would never see it or them again. We thought of the wild prairies of guns, canoes or the huskies mushing along the snow trail the sunset in the Pacific, Saturday afternoon at English Bay or the theatre all these thoughts would conjure up pleasant visions of congenial surroundings while there ahead of us in the full glare of the star shells was no mans land pitted every inch with shell holes full of stagnant water with many a body rotting in it. 5-25 all our guns are quiet a strange uncanny silence broods of everything broken only occasionally by a crump from Fritz - little he dreamed of the terrible holocaust soon to open up about him.

5-30 Every gun in the world seemed to have opened up together- the very ground shook the Ridge seemed to be aflame, we laid a barrage down just ahead of our first line of trenches at he foot of the Ridge - it was a wonderful sight one could see the wall of fire slowly ascend the Ridge & close behind line after line of our brave infantry boys advancing with their naked bayonets gleaming the lurid glare of the great barrage, I thought I had seen all Fritz's signals of distress but he still had a few new ones & these were going up frantically calling for aid from their reserves but it was no use - as the barrage passed over his trenches they were leveled & the barb wire blown out of existence, it was daylight by this time & the German prisoners were starting to come back to our cages already prepared for them & alas numerous Red Cross cars loaded with our wounded - it is really marvelous that any human beings could have come alive through such an inferno. The Ridge was in our hands & we were ordered out to advance the (here the paper is creased too bad to read), but we couldn't get very far. The ground was as if an awful earthquake had happened - the sights that greeted us on every hand is far too awful for pen to describe - but we took the Ridge & we still have it.

I hope Lillie I haven't sickened you with (here the paper is creased too bad to read) Remember me to the Ester your father & mother & husband & if you see the Troughams give them my warm regards.

Goodbye for the present believe me your affectionate brother Jack.