BOW VALLEY – A grand vision to establish an interconnected system of wildlands stretching from Yellowstone in Wyoming to the Arctic Circle in the Yukon is paying off in conservation gains.

A research paper published in Conservation Science and Practice on Dec. 1 shows more than 80 per cent growth in protected areas in the 3,400-kilometre long Yellowstone to Yukon (Y2Y) region in the last 25 years.

The study showed this sustained growth in protected areas and private land conservation was complemented by the expansion of endangered grizzly bears in the U.S. portion of Y2Y and an increase to 116 wildlife road-crossing structures not seen anywhere else in the world.

Researchers say demonstrating proof of the impacts of conservation is challenging, yet of growing importance in this field.

“I think we really need some good news… when you have a big vision and you are operating at the scale that wildlife needs, it does make a difference,” said Jodi Hilty, co-author of the paper and Y2Y’s chief scientist and president.

“When I first started my job about five years ago, I remember very specifically giving a talk to this audience and this guy said, ‘oh yeah, I was kind of part of the energy at the very beginning of Y2Y and always thought it was such a cool vision, but I never really knew what happened,’ and this was one of the reasons to try and do this in a scientific way.”

In the paper titled, Can a large-landscape conservation vision contribute to achieving biodiversity targets?, researchers tested for conservation gains by tracking several conservation metrics.

From 1968-93, there were 268 new protected areas, with an additional 149 from 1993-2018, for a total of 417.

“The most obvious win people often look at is how many acres have been protected and seeing an 80 per cent increase in protected areas is really important,” said Hilty.

The paper highlighted several case studies of protected expansion to illustrate Y2Y’s contribution to the growth of protected lands.

First, the 64,000 square kilometre Muskwa-Kechika Management Area (MKMA) in northern British Columbia was created in 1997.

The MKMA was negotiated through a multi-stakeholder group appointed by the B.C. government, two members of which had co-founded Y2Y in 1993. Y2Y also had a direct influence on the creation of four provincial parks in Alberta – Bow Valley, Spray Valley, Castle and adjoining Castle Wildland.

Perhaps the most significant gain, according to the paper, was the expansion of Nahanni National Park Reserve in Canada's Northwest Territories from 4,766 square kilometres, founded in 1972, to 30,050 square kilometres in 2009.

“The expansion encompasses the range of ~500 grizzly bears, two caribou populations, and significant biodiversity and cultural values,” states the paper.

Hilty said in the past two years there have been about 12 million new acres agreed upon through federal, provincial and territorial agreements with indigenous peoples to create new indigenous-led protected areas.

“To me, yes, we’re moving forward with ensuring that these lands will be intact in the future, but I think what has shifted most recently is we’re doing it as a society in a way that recognizes and respects indigenous rights,” she said.

The study concluded the gains in protected areas in the Canadian portion of the Y2Y region – where the bulk of the lands are public – have been mirrored by gains in private land conservation, which are especially important in the U.S. portion of the Y2Y region.

Quantifying rates of change in private land conservation easements is a huge challenge over the geographic scope of Y2Y, so the study highlighted two case studies that focused on restoring grizzly bear connectivity.

The first case involves private land conservation along the Elk River in B.C., negotiated between Y2Y and the private forestry company Tembec and then passed to the Nature Conservancy of Canada (NCC).

Y2Y raised more than $4 million of the $5.3 million-dollar project cost. Over the next 10 years, Y2Y worked in cooperation with the Transborder Grizzly Bear Project, NCC, and the Nature Trust of BC to make additional strategic private land purchases for grizzly bear connectivity along Highway 3 in B.C.

On the U.S. side of the border at the Yaak-Kootenai River confluence in Montana along Highway 2, Y2Y, and Vital Ground Foundation engaged in similar private land conservation.

Y2Y also worked with the Trust for Public Land to frame the rationale for $11 million that secured easements on 11,331 hectares of Stimson Lumber lands around the Yaak River confluence.

According to the paper, the Y2Y vision also helped inspire the Montana Legacy project which focused on restoring connectivity between the Northern Continental Divide Ecosystem and the Selway-Bitterroot, among other goals.

“This involved the purchase by TNC and Trust for Public Land of 130,000 ha of Plum Creek Timber lands, at $490 million, perhaps the largest private land conservation transaction in U.S. history,” states the paper. “These case studies demonstrate significant private land conservation in support of the Y2Y large-landscape conservation vision.”

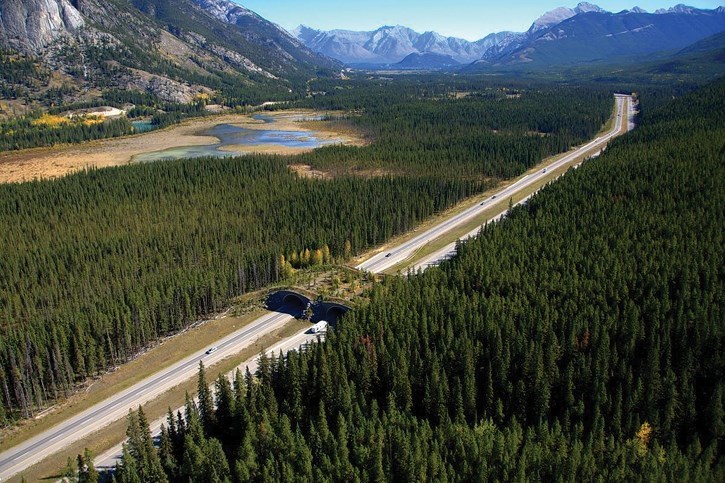

The paper points to at least 116 wildlife crossings on roads in the region, including in Banff and Yoho national parks, with more on the way as important conservation strides.

Hilty said the Alberta government is also building a long-awaited overpass and associated fencing east of Lac Des Arcs on the Trans-Canada Highway.

“Right here in our backyard, we have the most progressive wildlife crossing structures in Canada in Banff, and I think what is cool is we’re seeing that expand,” she said.

“That set of crossing structures represents something that other countries are looking at, certainly in the United States. There are also crossing structures around that world that have very clearly been inspired, but these are also the most well-studied crossing structures so they give us a lot of data about how well these work and which critters are using what kinds of structures.”

Hilty said B.C. is looking to have 11 crossing structures and the province of Alberta has committed to an underpass on Highway 3 through the Crowsnest Pass at Rock Creek.

“It is also interested in the NCC Jim Prentice Corridor and other crossing structures especially as that highway is been considered to be twinned,” she said.

In addition, the study showed sustained growth in protected areas and private land conservation has been complemented by the expansion of grizzly bear ranges in the U.S. portion of the region.

Hilty said Y2Y has been working with land trust and private landowners to voluntarily conserve private lands that are in the middle of key wildlife corridors.

“What is so exciting is that we’re actually seeing grizzly bears get to places that they haven’t been in decades,” she said.

“There are a number of bears that have moved from the border area of Canada and the U.S. all the way, for example, down into central Idaho, and they’ve been absent there for many decades,” she added.

“It’s a combination of protected areas, voluntary private land conservation and also coexistence work so that people can live with sometimes hard-to-live-with carnivores.”

Mark Hebblewhite, scientist and co-author of the paper, said the findings in the paper provide “a ray of hope” in times of headlines about climate change impacts on biodiversity crashes.

“Large-landscape conservation visions like Y2Y put into action represent powerful approaches to achieve biodiversity conservation at the scale that nature needs,” said Hebblewhite, a former Bow Valley resident who is now a professor of ungulate habitat ecology at the University of Montana.

As Canada and the U.S. advance concepts such as America the Beautiful and 30x30, Hilty said the Y2Y vision provides a model to address global biodiversity loss and climate change and progress offers a road map for how we can stem the loss of biodiversity in these countries.

“It is my hope that governments will look at this and realize that, yes, protected areas are really, really important, and that we actually really need to think about the scale that we’re doing our conservation planning if we want to address climate change and species loss,” she said.

The Y2Y vision was motivated by the shrinking distribution of grizzly bears and the journeys of gray wolves, including an individual wolf in the Canadian Rockies, known as Pluie, that covered an area of 100,000 square kilometres between near Banff National Park to Spokane, Washington, to the Bob Marshall Wilderness in Montana – and back.

Between 1991 and 1993, Pluie, a wolf radio-collared in southern Alberta, covered an area 10 times the size of Yellowstone National Park and 15 times that of Banff National Park.